J. Lammiman

The night is singing. I can hear the call of a whippoorwill. Frogs croak and belch a minor harmony of deep and low sounds. Fireflies light the night. Crickets chirp in tandem. It is dark but the whole world feels awake. It’s a different world than my daily worlds of school, church, family. I am 10, then 13, then 26. During spring and summer nights at my family’s rural home, I walk out to the end of our driveway and stand on our old country road and enter the night community. I don’t feel like I belong at school, church or even within my family unit, but this road, at night, is a place where that all falls away. It’s a place to which I belong.

Belonging is a concept often fraught with memories of being othered or feeling isolated or alone. It’s easy to remember times we felt we didn’t belong. But what does it actually mean to belong? How do practices of belonging shape our understanding of community development and climate action?

Belonging is first and foremost a relational practice. My experience of belonging to the night, the land, and that specific ecosystem was precipitated by relationship. I went outside every evening and this, over time, built connection. This connection between belonging and relationship can scale both up and down. For example, our bodies are a community that we sometimes take for granted. They are made up of cells, organs, microbiota, bacteria, etc. These communities work together inside each of us. When we get to know and affirm our bodies and their needs and desires, we can build a larger sense of belonging within ourselves.

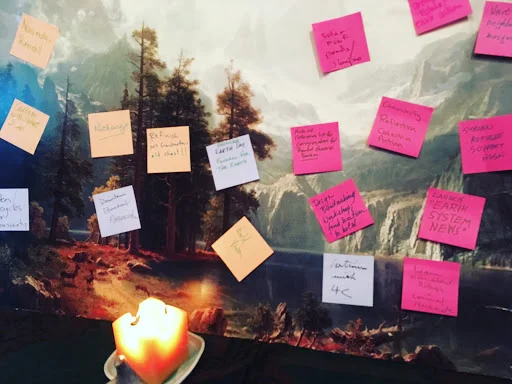

Building relationships is necessary for human communities to experience belonging. For community facilitators, our work is to invite individuals into deeper relationships with themselves, the ecosystems around them, and their communities. Belonging flows from proximity, intentional relationship, and practices that build trust and connection. When facilitating retreats on the topic of mental health impacts of Climate Change, I notice that most groups start with anxiety and nervousness. This is why we always spend time welcoming our bodies, our feelings, our life experiences, and each other. We then welcome our climate grief and whatever other emotions are present. We talk through how we want to be together and focus on co-creation of this time recognizing that we each have valuable skills, emotions and life experience to contribute in this space.

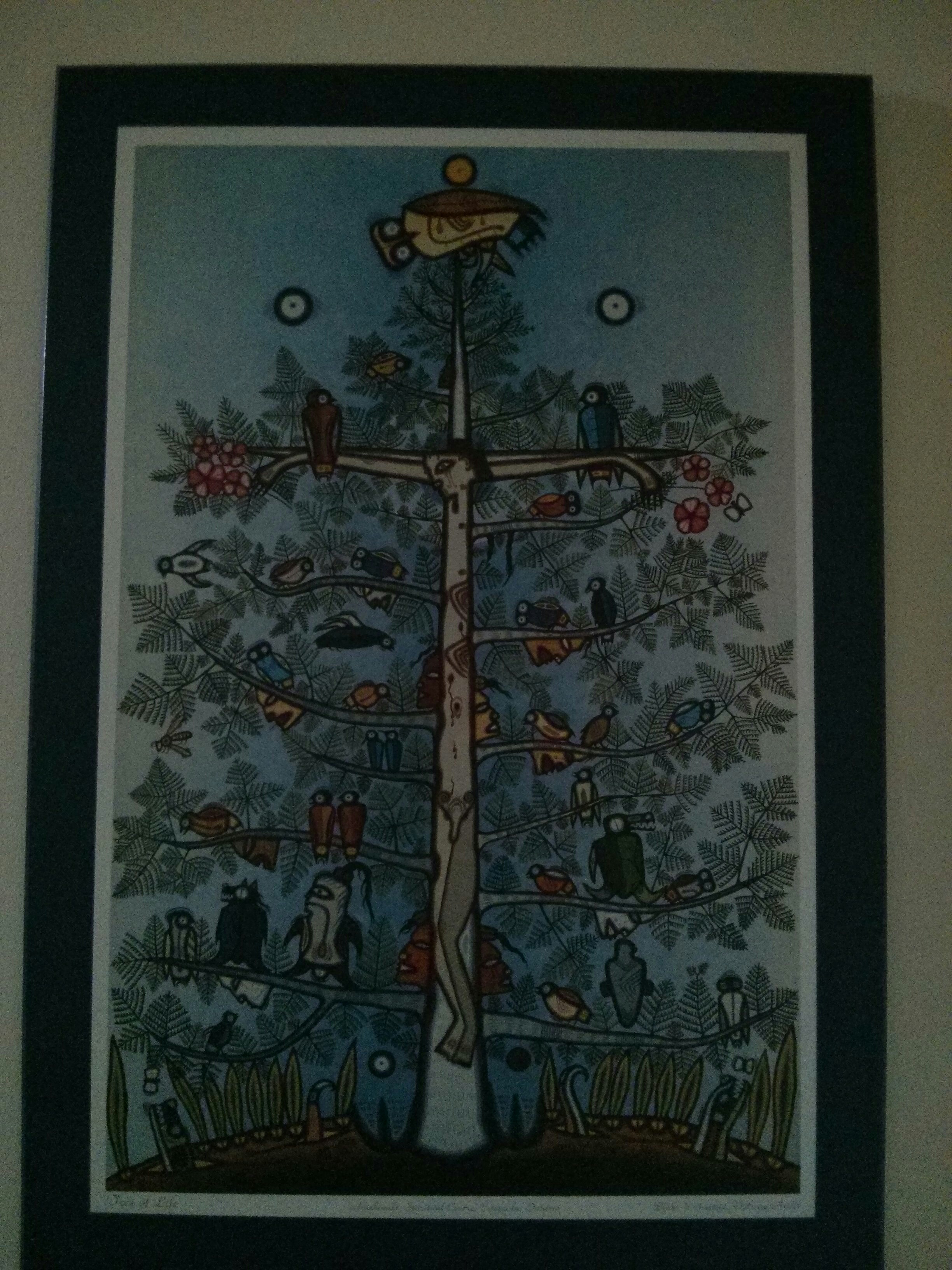

Alongside contribution, belonging also asks responsibility from us. To belong to something or with something is to participate in reciprocity. When we are in a relationship, whether it’s with land, our bodies, or human communities, those relationships involve sharing, receiving and responsibility. To belong to a place is to be in relationship with it and to be accountable to that relationship, is to foster it’s health, and to be in solidarity against forces that would seek to harm it. This relationship with land intersects with our own bodies, and our human communities. If the water in a watershed is contaminated, every plant, animal and human that draws water from that area is also impacted.

Belonging is communal and also a paradox. While we don’t always feel like we belong to human communities, we belong on this earth, simply by mere fact of our existence, and to belong is to recognize that we exist in community.

What does it mean to belong on a planet that is in peril? Everyday we awake to new impacts from the Climate Crisis. Rising sea waters, flooding in Pakistan, Libya, Nova Scotia, massive wildfires across the world and over 119 days of smoke in Calgary this season alone. The impacts of climate change are enormous and frightening and as humans, we need practices of belonging and recognizing our strengths in ways that help us to turn towards each other now more than ever. Shakhil Chaudhry, author of Deep Diversity, in a CBC interview said that emotions are the work of social justice. What keeps social change from happening are our emotional responses to it. It can be tempting to ignore, numb out or become paralyzed by fear and grief on behalf of ourselves and the planet. And yet, we need everyone to work towards ending climate change. Everyone belongs in this movement. Eco-elder, environmental activist and root teacher of the Work that Reconnects, Joanna Macy says, “If the world is to be healed through human efforts, I am convinced it will be by ordinary people, people whose love for this life is even greater than their fear.”

This frame acknowledges that climate action work is not solely any one of these dimensions, it’s all three dimensions working in tandem, and we need to continue cultivating community around all three of these dimensions. By getting to know our assets and strengths, we can better work with community members who have other strengths to share and bring our strengths to our communities.

Refugia exists to foster shifts in consciousness and support people’s mental health in connection to nature and in the face of the climate crisis, through facilitation, retreats and communities of practice and community gatherings.. This is personal for me because I believe that to stay engaged and aware living in the midst of climate change, we need places to acknowledge our emotions and find support for climate action.

Leading up to the creation of Refugia, I was living at a little retreat centre in the mountains. A large active clearcut was happening on the land around me and my community wouldn’t get involved in protesting it. I felt a lot of eco-grief which later burgeoned into climate grief, and I didn’t have places to process my intense emotions around the experience. It was out of this experience that Refugia was born, a collaborative place that invites people into emotions and practices care and compassion while extending curiosity to our inner stories, how they connect with nature, each other, and our communities. We also explore how those stories position us to question (and dismantle) the systems of oppression around us. For years I thought that I was a bad activist or community member because I wasn’t involved enough in direct action. The Dimensions of the Great Turning applied to climate action (pictured above), helped me to recognize my strengths in service to my communities. It reminds us that we all belong in this work and can bring our unique strengths to it.

It is late evening in October.I’m facilitating a climate grief retreat with a mix of climate activists, front line workers, and folks who care deeply about the world. Each comes with their own griefs. Many do not know each other. After introductions, agreements and sharing what draws each of us to this retreat, I invite the participants outdoors into a small clearing near the retreat centre. It’s late October and the night is cool and dark. From our small clearing surrounded by spruce and pine, we look up at the clear sky. The stars are here, the trees and small creatures, the prairie grasses. We all share in this moment. We welcome our bodies, our life experiences, our anxieties, and ourselves into this community for this weekend. We end our time outside noting the emotional responses that can arise when we are outside alone at night. We compare this to how different it feels to be outside in this moment, together.